(Just the first in a series of posts and retrospectives written and rewritten during and post trek)

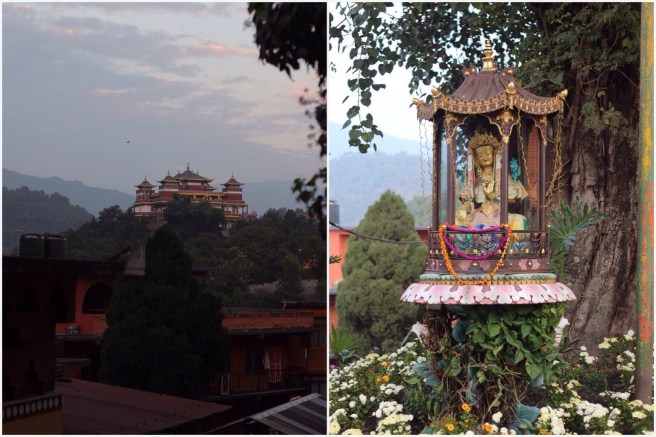

A small corner of window at a teahouse in Dzongla has become an unconventional gathering point. The patch of window is positioned right by the teahouse’s front desk, and a large crack in the glass has been covered with faded brown duct tape to keep out the wind.

For now, this single window looks out not only onto the mountains, but onto a changing political scene in Nepal.

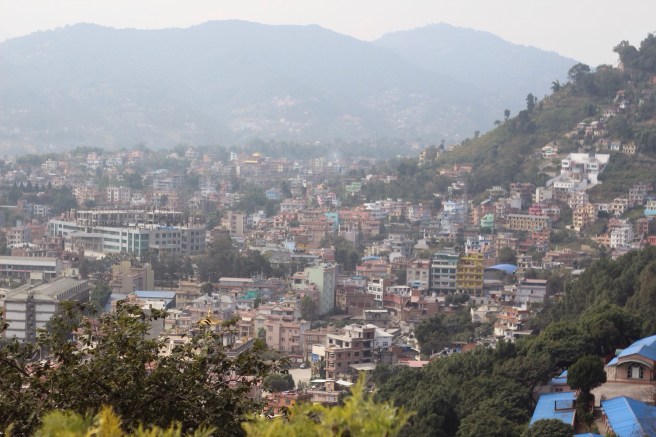

This window spot is where a handful of Nepalese sherpas, guides and porters, are getting their election news. It’s November 20, a day after the country’s national election, one that has been delayed several times over the past year. Some background: it has not even been a decade since Nepal became a parliamentary republic, having abolished the powers of the country’s long-time monarchy. Since the first Constituent Assembly elections held in 2008, the country has been repeatedly attempting and failing to write a new constitution.

With this most recent election, it will take days for the ballots to be counted and collected, both by computer and by hand.

But back to that corner patch of window.

Dzongla is located at 4,830 metres, and that patch of glass is the only place in the teahouse that gets cell phone reception. The election results are streaming through a cell phone that’s been put on speaker. It’s a Nepalese friend of the bunch relaying information from Kathmandu. It will be days before the Nepali Congress party (one of three main parties in Nepal, where there are a staggering 50+ political parties) is declared the winner, earning 105 out of the country’s 240 first-past-the-post seats. The former, post-civil war ruling party, the Maoist Communist Party of Nepal, saw its power wane, and ended up in third place, much to the thrill of my trekking guide, Gopal.

Here in the Himalayas, the Nepali Congress party is the most popular, with people telling me they put more focus on important priorities like building hydro-electric dams (much of the power in the upper altitudes comes from unsustainable kerosene, when there are multiple raging rivers whose powers could be harnessed) and increased access to clean water. One night in a town called Lobuche, a pro-Maoist guide was talking loudly about the party to his German trekking group. The tension in the room could have been cut with a knife. I was fascinated.

While lacking news and updates of my own country’s politics (wireless is possible while trekking to base camp, but it’s often expensive because it’s through a satellite connection), I became immersed and intrigued by the Nepalese political system.

Outside of this political-portal-in-the-form-of-teahouse-window, every night the guides and porters sit around the different teahouse stoves to discuss the day’s ongoings. I don’t understand the language, but I recognize the names of the political parties and the body language that follows the mention of each. I identify with the draw and appeal of ignited discussion, the dragging over of a plastic chair to join the conversation. Will this new Constituent Assembly be able to finally draft a constitution? Or will next year’s trekkers be hearing similar sentiments, more lost-in-translation political musings?

Time will tell, and I’ll be following from home.

I am both grateful and a little sad to have not been in Kathmandu during election day and the weeks leading up to it. Sad in a curious journalist sense. Grateful in the sense that the entire capital was virtually shut down because of a city-wide bandh (strike), where shops, offices, and schools were closed. The morning we left for our trek, our van to the airport was stopped by the military in preparation for political demonstrations later that day. Over the following week-and-a-half, those political protests grew violent, and people were injured. We take our peaceful political system in Canada for granted in so many ways. But to be fair to Nepal, at least national elections are something that everyone talks about, cares about, and feels invested in. Sure the political system here is disorderly, but maybe disillusionment and low political turnout requires a systematic reform just as much as chaos does.